The big news is that India’s fertility rate has now dropped below replacement level: it is 2.0 per woman.

That doesn’t mean that India’s population will start falling right away. India will still overtake China and become the world’s most populous country later this decade, with around 1.45 billion people, but in due course it will stop growing and start shrinking.

The delay is because human beings are not salmon: they do not spawn and die. Instead, they live on another thirty or forty or even fifty years after their children are born, so there is still a little bit of growth left in most Asian countries.

Let me explain, using the Dyer clan. I was the eldest of five children, which was a middle-sized family in Newfoundland at the time. We all lived to grow up, and on average we had exactly 2.0 children each – just below replacement level.

Those children all lived to grow up too, and it looks like they’re also going to end up with an average of 2.0 children each – but I and my brothers and sisters are all STILL alive.

Three generations of us, and where there were ten people in my generation (counting spouses), there are now thirty.

The baby boom stops there, because when my generation dies off, we will be replaced by the great-grandchildren. At that point the Dyer clan will finally have reached equilibrium – or even started to shrink a bit, if some of the grandchildren cut back on the child-bearing. It takes a very long time to stabilise if you stay at 2.0.

However, Asian populations are not stopping at 2.0. The phenomenon is most extreme in East Asia, where every country’s population is already in steep decline.

In South Korea, where the fertility rate is an astonishing 0.86 (less than one child per woman, on average), the population is going into free fall. At this rate, it will drop by half by the end of the century.

Same for China, where official statistics predict that the average woman will have only 1.3 children in her lifetime. At that rate, China will be down from 1.41 billion people now to 700 million by 2100, less than twice the population of United States at that time.

Even that may be too optimistic. Fertility expert Fuxian Yi, senior scientist in the obstetrics and gynecology department at the University of Wisconsin, recently estimated that China’s 2020 population was actually 1.28 billion, not the 1.41 billion recorded on the census, and that China’s real fertility rate is a lot less than 1.3.

The discrepancy arises, he says, because many of the children counted don’t exist. Local governments overstate their population to get more subsidies, especially education fees, from the central government, and some families buy extra birth certificates online on the black market because there are over 20 social benefits linked to a birth registration.

If Dr. Yi is right, then the United States, despite a fairly low growth rate (443 million in the year 2100), may have about the same population as China by the end of the century. Japan’s fertility rate is 1.35, but that still means its population will fall from 125 million now to 75 million by century’s end.

Most of South and Southeast Asia is already below replacement level (Vietnam 2.0, Bangladesh 1.9, Thailand 1.5). The rest are almost there (Indonesia 2.2, Myanmar 2.15, Sri Lanka 2.15). Apart from the Muslim countries of the Greater Middle East (Pakistan to Syria), the only big Asian country still growing fast is the Philippines (2.5).

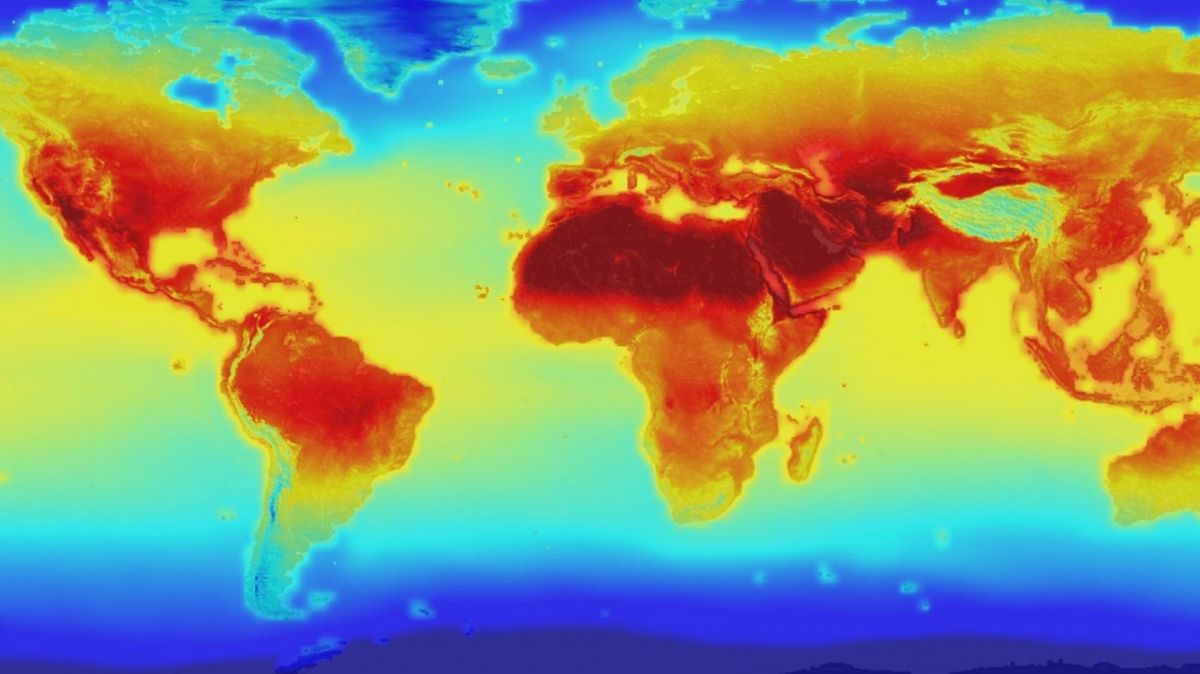

Populations in Europe are stable or gently falling, and in the Americas almost every country has a growth rate of less than 1%. The only world regions still growing fast are the Middle East and Africa, where population growth rates are between 1.5% and 3%.

Project those numbers forward to 2100, even allowing for a gradual decline in Middle Eastern and African fertility rates (which is not currently happening at all), and just these two regions will contain half the population of the planet at the end of the century: more than four billion people.

Except for the Arab oil states and a couple of middle-income countries like South Africa and Iran, unfortunately, none of these countries has a per capita GDP of more than $5,000 a year, and their incomes are barely keeping up with population growth. It will be a very divided world.